We have demonstrated in Misconception #1 that the commonly held Bernoulli explanation of lift is physically incorrect. In fact, outside of a confined space, such as a pipe, the Bernoulli equation has no application in the physical world. In particular, fast-moving air will always have the same pressure as the surrounding environment.

Hopefully, we have convinced the reader that the wing moves through Still Air, accelerating air down to produce a lifting force up. Here, the Bernoulli equation is not even referred to. These two descriptions of lift will be briefly reviewed below.

If that were all there was to flight, the story would be complete. But the fly in the ointment is that AEs do use the Bernoulli equation in their calculations. And to top it off, they work in wind tunnels where the air is definitely flowing over the wing. We will put these conundrums to bed here.

The Bernoulli Hypothesis of lift

Briefly, there are a few requirements of the Bernoulli explanation of lift. Here is an abbreviated list:

- The wing must be cambered on top so that the air going over the top has to travel farther.

- Faster-moving air has a lower static pressure, producing lift.

- Since the Bernoulli equation is a statement of the conservation of energy, no work can be done

Here is a rebuttal of these requirements.

- One complaint is that there really has never been a convincing argument why the air should go faster over the hump. This is often called “Hump Theory”. Then there is the problem that wings can fly upside down. And to top it off, Misconception #2 shows that the shape of the wing has a lot to do with cruise efficiency and stall characteristics; it has nothing to do with lift.

- As discussed in Misconception #1, faster-moving air will always have the same static pressure as the surroundings. If this were not true, the static port on the airplane would be useless, and your ears would pop when you open the window on a moving car.

- This condition is usually conveniently overlooked. When it’s considered, the argument is usually that the lift does not require work, and the energy loss is due to the wingtip vortices. Clearly, the range of an airplane depends on the payload.

The revelation that got me questioning this description of lift was that it doesn’t explain how an airplane corrects for changes in speed, load, and air density

The Newtonian Description of Lift

The first point to make is that all airplanes fly in still air, just like a hot air balloon. An airplane on top of the clouds with only a magnetic compass and an altimeter has no way of determining the strength or direction of the wind. It may be flying with a 200-mph headwind or a 200-mph quartering tailwind. It is flying in still air. The wings are cutting through the air, not the air flowing over the wings. It’s like riding a bike on a day with still air. When you move, there is a breeze in your face. If you stop the breeze stops. You are the one doing the moving.

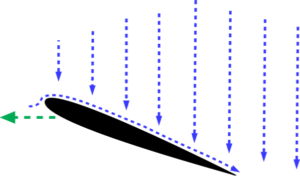

Lift on a wing is simple. A solid surface moves through the air and produces lift. This is not Rocket Science. Referring to Figure 1, a wing with some angle of attack is moving through still air. The descending upper surface draws air down. Newton’s third law says that since there is a force on the air, there must be an equal and opposite force on the wing; i.e., lift. The lift is adjusted with speed and angle of attack, as discussed in Lift Details.

Newton’s second law tells us that the lift on any wing is equal to the rate air is accelerated perpendicular to the direction of motion times the velocity of that air. The amount of air diverted is measured in tons per second, even for a small airplane. This fact is certainly not addressed in the Bernoulli explanation of lift.

Aeronautical Engineers (AE) and Bernoulli

Now we have two conundrums to face. The first is that in the Newtonian description of flight, the wing moves in still air, accelerating air straight down. The AEs work in a wind tunnel where the wing is stationary, and the air is moving. The second conundrum is that we have stated that the Bernoulli equation has no place in the physical world, outside of a confined space such as a pipe. Yet the AEs use it in their calculations. To address the still air versus the wind tunnel problem, we will start with a thought experiment.

Still Air vs Wind Tunnel

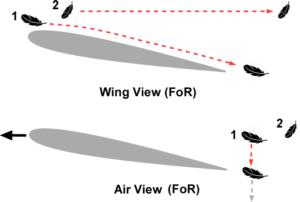

Let’s assume that a high-flying goose loses two downy feathers. As they slowly drift down, an airplane passes the feathers. See Figure 2. The wing passes, say 1 foot, under feather #1. Feather #2 is approximately the same height as the first feather, but far enough away not to be disturbed by the wing. The “wing view” or the pilot’s view shows the first feather streaking back and coming off at a downward angle. That’s the downwash. Feather #2 streaks back at the same speed but at a constant altitude. In this frame of reference, one can imagine applying the Bernoulli principle. After all, it is the wind-tunnel frame of reference.

Now let’s look at the same event, viewed from a hot-air balloon at rest with the air. We have shown that an airplane flies in still air. So is the balloon. Feather #1 goes straight down as we understand it should. The air is accelerated perpendicular to the flight path to produce an equal and opposite upward force. Feather #2 is, of course, stationary. Since no air flows over the wing, the Bernoulli principle cannot be applied.

So, there we have it! The Bernoulli explanation of lift is “rest-frame dependent”. That is, the physics varies with the motion of the observer. But the physics of lift cannot be rest-frame dependent. The physics of the interaction of the wing and the air does not depend on the observer. Also, the Newtonian view of lift, with flight in still air, and the wind tunnel view are just views in different reference frames. If a feather with a small camera were to move with the air in a wind tunnel, the air motion around the wing would be the same as in Figure 1.

Bernoulli and Calculations

When confronting someone on the applicability of the Bernoulli equation, more often than not, one will hear that it is used by AEs in the calculations. Certainly, this is the retort of the AE. That is a true and difficult argument to refute. But it still has nothing to do with the physics of flight.

The Bernoulli equation is a statement of the conservation of energy. But outside of a confined space, such as a tube, energy cannot be conserved. This is particularly true for flight. An airplane in cruise comes along and accelerates tons of air per second down. That is doing work. The energy to produce lift goes as the load on the wings squared.

The Bernoulli equation, or something like it, is used in AE simulations. But since energy must be held constant, it is only applicable for simulations of 2-D or infinite wings. Two-dimensional wings and infinite wings produce lift without doing work, so they do not violate the restrictions above. But you probably won’t see either wing design on airplanes in the sky.

Now comes the simulations of 3-D wings, that is real wings, which require work to produce lift. The Bernoulli equation is not directly applicable here, though they think they are using it. In the simulation, energy is lost due to induced drag that is not corrected for. The wing is slowing down. But one of the requirements for the application of the Bernoulli equations is that the system must be in equilibrium. That is, nothing is changing. They get around this by taking a snapshot of the system. They catch it at a moment in time. Then they apply an equation like Bernoulli’s, but total energy is not held constant. They don’t seem to appreciate that they’re taking data on a wing that is losing energy, is slowing down, and is not in equilibrium.

Takeaway

The Bernoulli equation is a mathematical tool that can be used in very well-defined calculations. It has utility in calculations, but when used to describe the physics of lift on a wing, it is terribly misapplied. The Bernoulli equation has nothing to do with the physics of lift.