Air Pressure

Pressure is a force on a surface. Our interest here is air pressure rather than pressure in other fluids. Air pressure puts a force on a surface perpendicular to that surface, and the units of measure are force per unit area. A typical unit of pressure in the US is pounds per square inch. Believe it or not, the pound is a unit of force, not of mass. That is why the thrust of a rocket is given in pounds.

Air pressure is caused by the air molecules striking the surface. There are only two ways that an air molecule can interact with a surface: producing a force perpendicular, which is pressure, and sliding along the surface, which is friction. The pressure at the surface of the Earth is 14.7 pounds per square inch (psi). That doesn’t have much meaning to us. How about the pressure is 1 ton per square foot? Under that dreadful pressure, why aren’t we crushed? It is because we have the same pressure inside. The fish at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest spot in the ocean (35,000 feet), are under a pressure of over 1000 tons/ per square foot, or 6 tons/square in. Just like the fish in the deep don’t sense how heavy water is, we are pretty ignorant of the weight of air. A cubic yard of air weighs about 2 pounds. A cubic meter of air weighs 1 kilogram (kg) or 2.2 lbs.

There are two common measurements of air pressure: Absolute and gauge pressure. Atmospheric pressure is absolute pressure, which measures the pressure against a vacuum. On the other hand, gauge pressure is the most common measurement and is measured against the surrounding air pressure. A tire is a good example. If one fills the tire to the gauge reading of 30 psi at sea level, the absolute pressure in the tire is 44.7 psi (30 +14.7). Drive the car to 6,500 feet, where the absolute pressure is 3 psi lower; the absolute pressure in the tire will still be 44.7 psi, and the gauge pressure will now read 33 psi.

A third measure of pressure is differential pressure. It is a measure of the difference between two pressures. Gauge pressure is a differential pressure. The lift on a wing is determined by the differential pressure across the upper and lower surfaces of the wing.

Although air pressure is a simple concept, the way it is often presented in flight is very confusing. Air pressure is just the force placed on an object by the striking of air molecules and friction. The lower pressure on top of an airplane wing does not “suck” the wing up. It reduces the force on top of the wing so the pressure on the bottom can lift the wing. When a can is collapsed by drawing the air out, it is being crushed by the outside ambient pressure.

There are three pressures associated with flowing air. The first thing that we will discuss is static pressure. This is what is meant when people refer to “air pressure”. It is the pressure one would measure in a building or riding in a hot-air balloon.

The second is dynamic pressure. This is not technically a pressure but has the dimensions of pressure. It is due to the motions of the air. It cannot be measured directly. When you stand in a strong wind, the side the wind is striking is the sum of the static and dynamic pressures. Your downwind side feels only the static pressure. So, it is the dynamic pressure that is trying to push you over. The differential pressure from one side to the other is the static pressure on one side and the static pressure plus the dynamic pressure on the other side. This is how an airplane’s airspeed indicator displays the aircraft’s indicated airspeed (IAS).

Take, as an example, a large mass of air moving at 35 mph across the ground. If one were to ride in a hot-air balloon, the balloon would become part of the mass and move with it. The air around the balloon would appear still, and one would be experiencing the static pressure of the air mass. A person walking against the wind on the ground would have a very different experience. The person would experience static pressure that is the same whether the air is moving or not, but also the force of the dynamic pressure, making walking difficult.

When a high-speed jet of air (or water) comes out of a nozzle, its static pressure adapts to the static pressure of the surroundings, but the dynamic pressure remains the same.

The third pressure is the total pressure. which is the sum of the static and dynamic pressures. If you hold the total pressure constant, then you have the Bernoulli equation.

The Pitot Tube

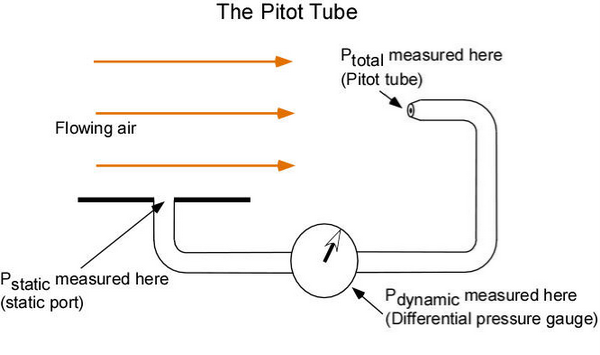

The airplane’s instrumentation measures the indicated airspeed by exposing two ports to the airflow. The first is the static port on the side of the fuselage. See Figure 1. The static port measures the static pressure independent of the airplane’s speed. This port is also used to measure the altitude and to provide air pressure to other instruments. The static port is usually on the side of the airplane fuselage near the front, though it is also occasionally placed on the side of the Pitot tube itself. Figure 2 shows a Pitot tube mounted on the bottom of a wing.

The Pitot tube faces directly into the air flow as shown in Figure 1. This measures the total pressure, which is the sum of the static pressure and dynamic pressure. Both the static port and the Pitot tube are connected to a differential pressure gauge, which is the gauge that measures the difference between the two pressures. The result is that the static pressure is subtracted from the total pressure, yielding the dynamic pressure, which is related to the aircraft’s airspeed. The differential pressure gauge is calibrated in speed. This is the airspeed indicator. The “indicated airspeed” must be corrected for air density and temperature to give “true airspeed”.

Takeaway.

There are at least six measurements of air pressure.

For still air:

- Absolute pressure

- Gauge pressure

- Differential pressure

For flowing air:

- Total pressure

- Static pressure

- Dynamic pressure